Civil War women soldiers were not officially allowed to serve as soldiers for either side during the war.

Those who enlisted disguised themselves as men.

With today’s standards of hygiene and physical medical exams this would be impossible to do, but Civil War physical exams were casual and did not require the person examined to strip.

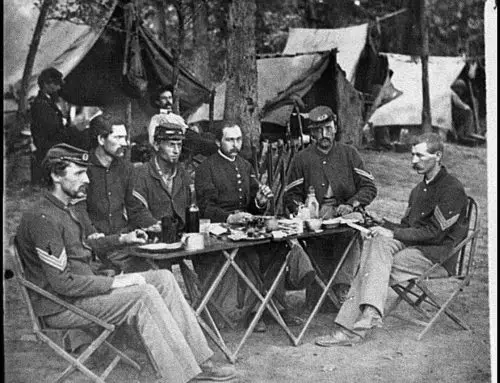

It was not unusual for soldiers to refrain from undressing in front of one another; soldiers often bathed in their underwear and seldom changed it.

Achieving a “male voice” and coping with lack of facial hair might seem at first glance to present greater difficulties, but the numerous underage boys in the military made it easier for females with “boyish voices” and little facial hair to go undetected.

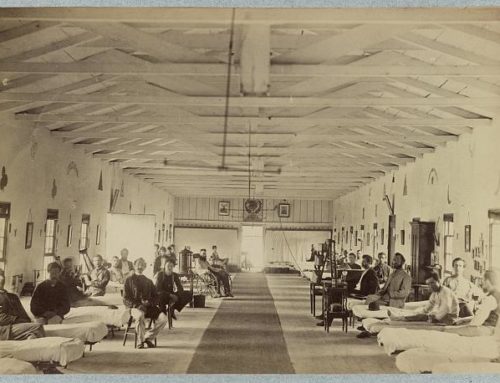

Most Civil War women soldiers were not discovered until they fell ill or were wounded.

Mary Owens served in the Union army as John Edwards for a year and a half before she was discovered.

Loreta Velazquez served as Confederate Lieutenant Harry Buford. Velazquez was one of the few females soldiers to leave her own written record of her service; she published her story in 1876, although historians dispute some of her claims.

Women had various motives for joining the army. Some did so from loyalty to their side, others from a sense of adventure. Some, such as Satronia Smith Hunt who joined an Iowa regiment when her husband did, simply did not want to leave their soldier husbands, while poverty pushed others to join to gain a soldier’s meager pay.

Albert D. J. Cashier and Sarah Edmonds are two of the most well-documented female Civil War solders.

Cashier joined the Union army in August 1862 and served until after the war ended. Cashier was an unusual female soldier; she apparently felt more comfortable living life as a man than as a woman and lived all of her adult life posing as a man.

Her sex was not revealed until a year before her death, when the doctor at the Quincy Illinois Soldier’s home where she was staying, discovered the truth.

Sarah Edmonds joined the Union army in 1861 and saw action at First Manassas, Fredericksburg, and Antietam.

Fearing discovery when ill with a fever, she disserted in April 1863. Edmonds was a more typical female soldier, for she went back to life as a woman after the war and married L. H. Seelye in 1867.

However, Edmonds was untypical in that she successfully convinced the government to give her a pension for her military service.