Civil War prison camps were terrible places, when they saw the photographs of emaciated Andersonville prisoners who literally looked like skeletons, northerners were shocked and horrified. Many claimed the conditions at Andersonville were a cruel conspiracy against northern soldiers, deliberately perpetuated by Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and other Confederate leaders.

The name Andersonville became synonymous with the horrors of Civil War prison camps, but in reality prison camps on both sides were poorly managed, horrendously overcrowded, and disease-ridden.

Although some prison commanders on both sides were deliberately cruel and vindictive to those in their charge, the conditions in Civil War prisons were primarily due to circumstances and poor planning, rather than a calculated conspiracy to kill prisoners.

Early in the war, leaders from both sides agreed to a cartel that allowed for the exchange of prisoners.

By this gentleman’s agreement, paroled prisoners were not supposed to return to the fighting until they had been officially exchanged. The sheer numbers of captured soldiers made paroling prisoners a practical option, as well as a humane one.

There was always the chance that paroled prisoners would immediately return to fighting and many of them did.

In addition, the exchange system was somewhat complicated; officers required more than one private in exchange and the higher the officer’s rank, the more enlisted men were needed to be exchanged for them (somewhat like a chess game).

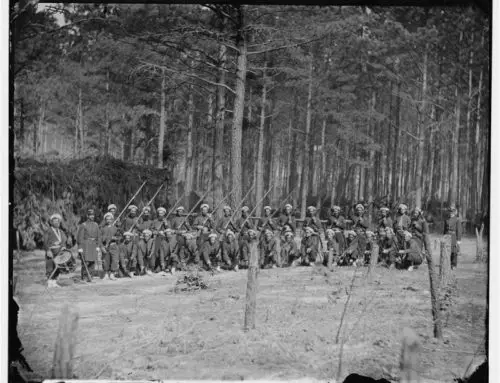

As the war progressed, prisoner exchanges slowed. Once black soldiers began fighting for the Union, the situation became even more complicated. The Confederacy refused to acknowledge black Union soldiers and their white commanders as prisoners of war, calling the black men “rebel slaves.” As “rebel slaves,” African American prisoners of war were subject to harsh punishment and even execution.

In response, Lincoln declared that he would execute a Confederate prisoner of war, for every Union prisoner executed. This generally prevented black soldiers from being executed, but they were still treated more harshly than white prisoners.

The South refused to exchange blacks in return for Confederate soldiers. In 1864, Grant refused to exchange any more prisoners until black and white soldiers were treated equally.

The slowing and eventual stop of the prisoner exchange meant that the hastily constructed Civil War prison camps in both the North and the South were tremendously overcrowded by 1864.

The situation was not nearly so bad at the war’s beginning, when prisoners were rather rapidly exchanged and many were paroled without seeing a prison camp.

At the war’s outset, prison planners did not anticipate the conflict lasting for long. Most Civil War prison camps were poorly planned and some were situated in damp locations which made disease more likely.

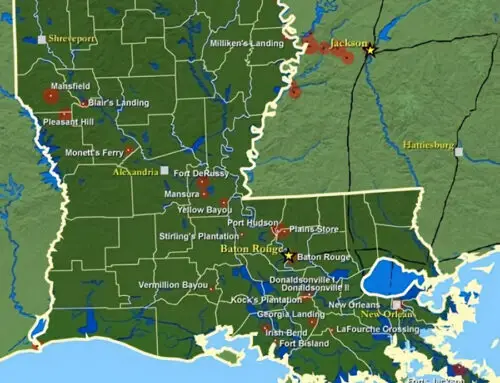

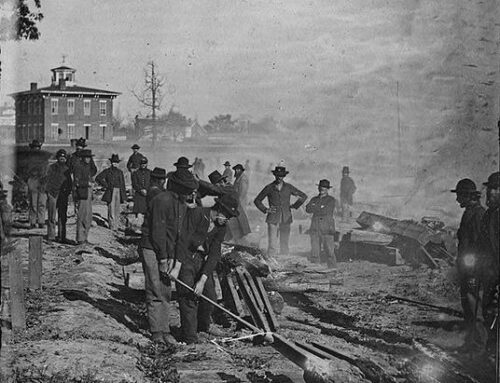

One of the first Confederate Civil War prison camps was in Salisbury, North Carolina. Union prisoners from the First Battle of Manassas were held there.

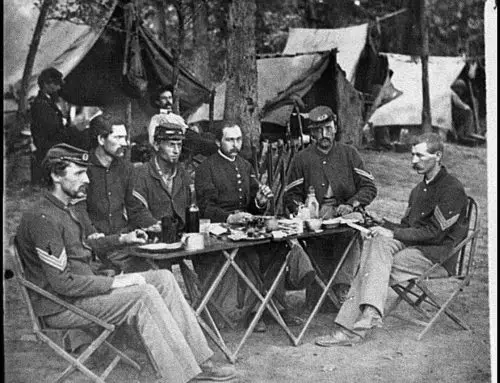

Although prison life was rough, the first prisoners enjoyed the freedom of playing baseball in the large prison yard.

The prison was also used to detain army deserters and Southern political prisoners. It soon became overcrowded, holding 10,000 prisoners, when it had been designed for 2,000.

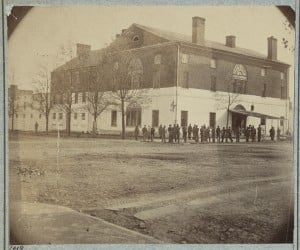

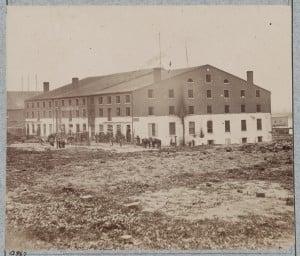

One of the first Union prisons was the Alton, Illinois Federal prison, which began receiving prisoners of war in February 1862. Since Alton was an established prison with buildings, prisoners there did not suffer the exposure to the elements common in so many prison camps.

However, prisoners did suffer from scurvy, anemia and other diseases brought on by malnutrition. This is ironic, since unlike the South, Alton never experienced a food shortage.

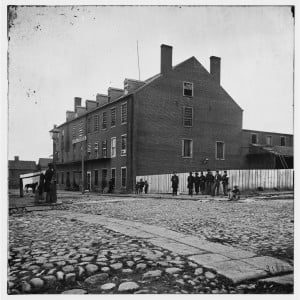

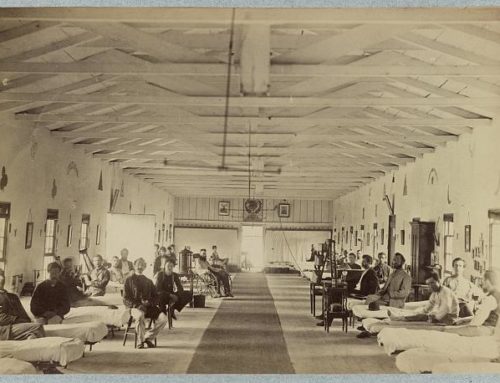

The worst Civil War prison camps were those which were set-up in haste, with scant thought to proper construction or sanitation. Belle Isle Prison in Richmond and Point Lookout in Maryland were the only two major prison camps intended to house prisoners solely in tents.

Tents were provided to house three thousand prisoners at the Confederate Belle Isle, but their numbers soon rose to twice that. Point Lookout was one of the worst Union prison camps.

Tents were provided to house 10,000 men, but the prison population fluctuated between 12,000 and 20,000. The men had to sleep outdoors in Maryland’s inclement weather even if they lacked tents.

There were stories of brutality by the camp’s black prison guards. As many as 14,000 men may have died of disease at Point Lookout during its two years of operation.

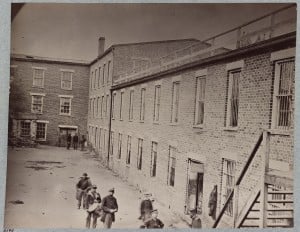

It is generally agreed that Point Lookout was the worst of the Union Civil War prison camps. Elmira Prison in New York was almost as bad, though not as large. Nearly a quarter of the 12,123 Confederate prisoners sent to Elmira died.

Many of the prisoners had to sleep outdoors with scarcely any blankets or adequate clothing. The United States commissary-general of prisoners, Col. William Hoffman was vindictive and deliberately allowed poor conditions and starvation at Elmira.

However, vindictiveness was not the rule in either the northern or southern prison camps. Henry Wirz the head of the notorious Andersonville Confederate prison was executed after the war for his failure to provide better living conditions, but there is no evidence that his failure was either malicious or deliberate.

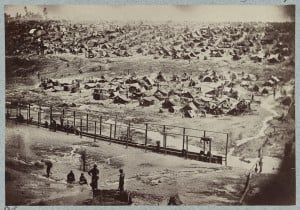

There were simply too many prisoners and not enough food, clothing, medicine, or tents to go around. Andersonville existed for a little over a year and over 45,000 Union troops were imprisoned there. Nearly 13,000 prisoners died of disease or starvation.

Rations at Andersonville were dreadful; prisoners received slightly more than a pound of cornmeal and a pound of beef or a small portion of bacon each day, but this was what the prison guards received as well and Confederate combat soldiers were subsisting on the same inadequate rations.

However, nutrition for soldiers in both the North and the South was inadequate much of the time. Several men from the Army of the Potomac died of scurvy while training near Washington, since their diet lacked vitamin C.

Though medical science was unaware of vitamin C, doctors in the British military had long before discovered that citrus fruit prevented scurvy.

Understandably, under the crowded conditions, medical care was woefully inadequate and many prisons lacked hospital facilities. Ignorance of proper hygiene contributed to disease as well. Many of the camps were situated in areas with poor drainage and wastes soon accumulated.

During and after the war, many people on both sides thought that poor prison conditions were due to malice. Historians now believe the failure of Civil War prison camps was due to human error, but not generally to malice.

Housing so many people adequately was next to impossible in peacetime conditions; the added burden of war, made to it virtually impossible.