April 25th – May 1st 1862

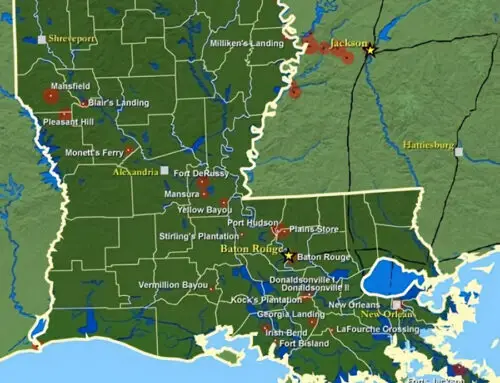

The battle of New Orleans was the start of the Anaconda Plan; this was the name of the operation set-up by the Union to divide the Confederate States.

The statuesque crescent city, the jewel of the Confederacy, if this city could be taken and then occupied, the war would be nearing its end. This was the thought process of General Winfield Scott, the embattled Union General, who was the commander of the northern forces in the south.

Scott utilized the naval military talents of Flag Officer David G. Farragut and his West Gulf Blockading Squadron.

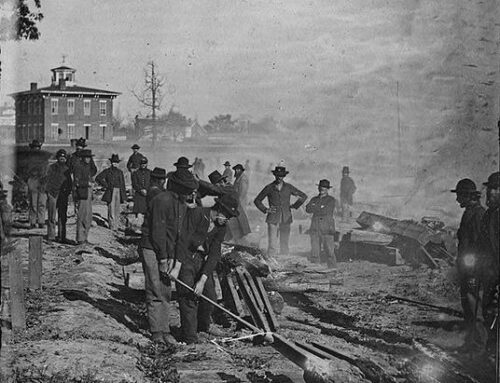

The assault was initiated at the mouth of the Mississippi River and involved the taking of the two passage forts, Jackson and St. Philip. Farragut was able to bombard the forts and take both of them within five day’s.

The fighting was brutal and intense, but in the end, the Confederates could no longer withstand the constant bombardment from Farragut’s big guns. The surrendering of the passage forts marked the end for New Orleans and the actual battle had been won.

Farragut sailed into the harbor of New Orleans, 13 ships abreast, unchallenged by anything the Confederates could muster, on April 25. The city had fallen and the war was now in grave jeopardy of being lost for the Confederates. The Battle of New Orleans was important for another reason as well. The occupied city had as it’s new political leader, a man they would refer to as “Beast Butler”.

The army entered the city of New Orleans under the command of Major General Benjamin Butler. General Butler would later become the Military Mayor and his administration would be both applauded and appalled. The city enjoyed a fruitful existence under the watchful eye of Butler, but it was in this administration that curious laws and regulations were imposed.

The women of the city were not to insult any Union soldier under threat that she would be considered a “woman of the evening”. Harsh and strict, the new Mayor would be accused of pilfering silverware from the stately southern homes in which he would stay, earning the dubious title of “Spoons”. Such acts only added fuel to the fire for a city, a country that was so torn apart from the un-civility of the war.

It was on June 7th, 1862 that Butler would push the envelope a bit too far and execute a resident for the crime of tearing down the US flag that had been hung on the US Mint building. For this execution, the President of the Confederate States, Jefferson Davis, would label Butler a “felon”. The anger towards Mayor Butler would not be from the southern side of the fence, the north would also condemn Beast Butler, and order his removal.

The battle created such a stir that the affects were felt as far away as the United Kingdom and France. Both southern allies denounced the treatment of women in New Orleans by Butler and vowed to put an end to this “barbarianism” militarily is necessary. The Union could not afford to waste any energy on fighting another army, especially the size and strength of the English and French. Butler was relieved of his position and an international incident was avoided.